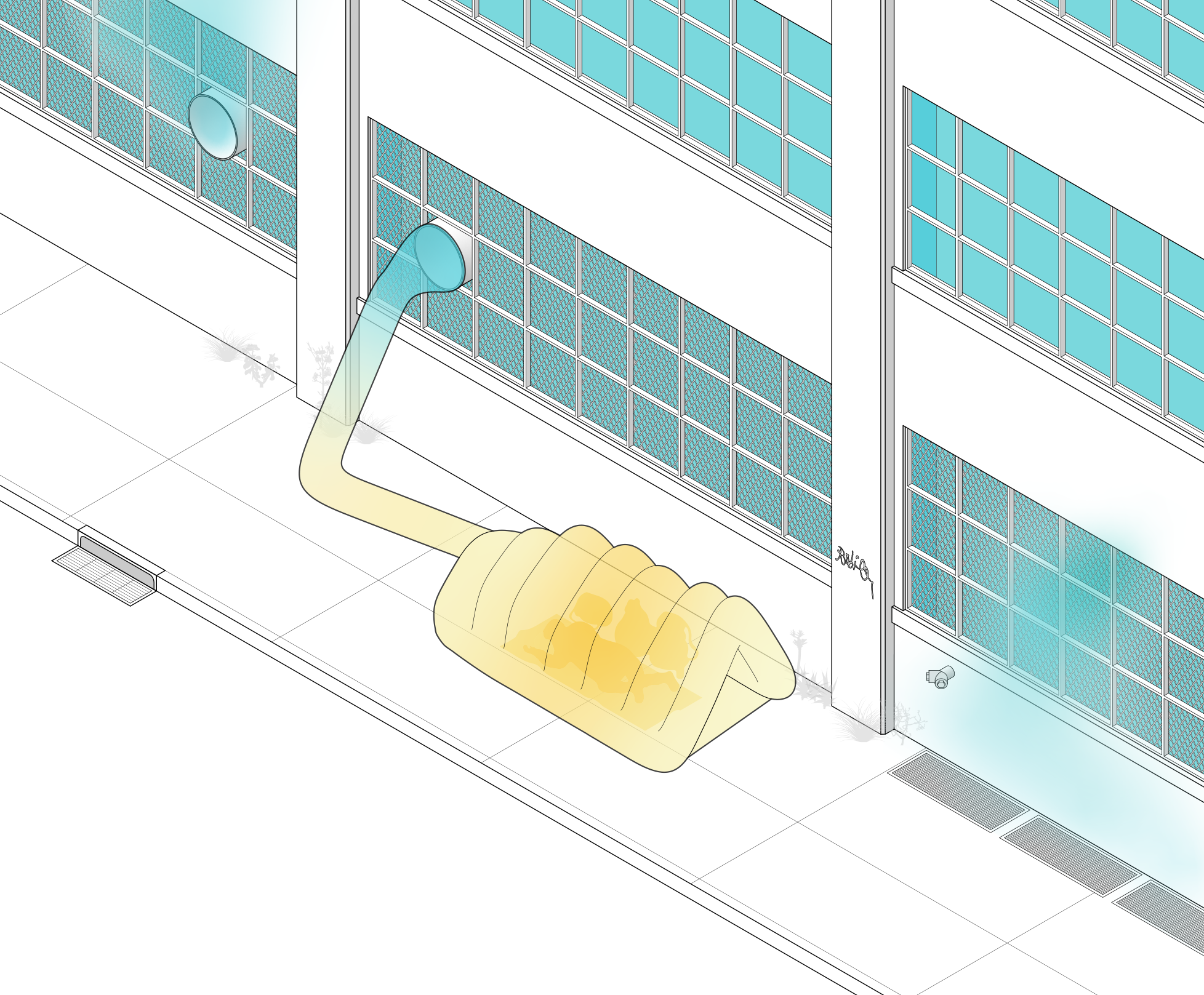

BUILDING AIR EXHAUST WITH INFLATABLE SHELTER

paraSITE SHELTERS

Multiple locations

1997

Michael Rakowitz in collaboration with shelter occupants

Piggybacking Tactic

Capture a Waste Stream

In 1997, the city of Cambridge, Massachusetts, sought to deter the unhoused from sleeping on heated metal grates near Harvard Square by tilting them at an inhospitable angle. To alleviate the challenges this created for those who had no choice but to sleep on the streets in the winter, the artist Michael Rakowitz began making what he called paraSITE shelters—temporary plastic tents that could be connected to a building’s exhaust vent. The air from the vent would inflate the structure while providing warmth for the occupant. The shelters were easy to transport, and the transparent plastic provided occupants with a sense of safety by allowing them to remain visually aware of their surroundings while inside. Rakowitz regarded each occupant as his “client,” working with them to design their inflatable shelter according to their particular needs.

It’s important to note that Rakowitz himself saw these shelters as little more than “band-aids” in addressing the plight of the unhoused in the contemporary city—at best a temporary reprieve from deprivation. But like a bandage, Rakowitz believed, the paraSITE shelters would address the wound while also making it visible to others. Both their transparency and their clear status as an unviable housing strategy for the long-term provoke bystanders to confront the extreme inequities of urban society. Real change, Rakowitz believed, would need to come from policymakers and the public, and these shelters were an appeal to the collective conscience. In this way, the paraSITE project highlights the practical limits of piggybacking practices as mechanisms for social justice. They are immediate and necessary tactics for working within the margins of the dominant social and economic paradigms, but they are not a replacement for political efforts to achieve durable social change.